- Research Article

- Open access

- Published:

Scleractinian corals from the Lower Cretaceous of the Alpstein area (Anthozoa; Vitznau Marl; lower Valanginian) and a preliminary comparison with contemporaneous coral assemblages

Swiss Journal of Palaeontology volume 141, Article number: 3 (2022)

Abstract

From the Vitznau Marl (lower Valanginian) at the locality Wart in northeastern Switzerland (Alpstein area), 18 species from 17 genera and 13 families are described, including the genera Actinaraea, Actinastrea, Adelocoenia, Aplosmilia, Axosmilia, Complexastrea, Cyathophora, Dermosmilia, Fungiastraea, Heterocoenia, Latiastrea, Montlivaltia, Placophyllia, Pleurophyllia, Stylophyllopsis, Thamnoseris, and specimens showing affinities to solitary stylophyllids. The corals from the Vitznau Marl were derived from a limestone–marl alternation that is fossiliferous and clay-rich at the base (Vitznau Marl), containing crinoids, bryozoans, and sparse reworked corals and sponges. The coral fauna is distinctly dominated by forms belonging to the category of lowest to no polyp integration (50%), followed by species of the cerioid-plocoid group (33%) and forms having the highest polyp integration (thamnasterioid; 17%). With regard to polypar size, the Wart fauna is dominated by corals having large-size (> 9 mm) polyps (= 39%), followed by corals having medium- (> 2.5‒9 mm; 33%) and small-size polyps (up to 2.5 mm; 28%). Based on morphological features, the fauna from the Vitznau Marl closely corresponds to coral assemblages that are subjected to near-chronic, moderate sediment-turbidity stress that is punctuated by high-stress events, and that are largely or entirely heterotrophic. No coral fabric was observed that would suggest a biohermal development. But in a very small number of places, structures are present which might be fragments of crusts of microbialites, pointing to the hypothesis that at least a few of the corals might have been a part of some kind of bioconstruction. At the species-level, the fauna of the Vitznau Marl shows either no or very little affinities to other Valanginian assemblages such as to the fauna of Hungary (4.3%), followed by the associations of Ukraine, Switzerland (non-Vitznau), Spain (SpII), and Bulgaria. At the genus-level, the Wart fauna shows low correspondence to the fauna of Spain (SpII) (14.5%), followed by the assemblages of Hungary, Bulgaria, and Ukraine. In addition to the Vitznau Marl corals, an account of all Valanginian coral faunas published before early 2021 is given, including their paleogeographic distribution, as well as their taxonomic and morphological characterization. For this preliminary study, a total of 206 coral species belonging to 97 genera found in the coral assemblages of the Valanginian were included. At both the genus- and the species-levels, colonial taxa are most abundant (colonial genera: 89%; colonial species 90%). The vast majority of the Valanginian genera already occurred in older strata. Only 11 genera (out of 97 = 11%) are newly recorded. The Valanginian faunas having the largest number of solitary taxa lived in both (sub-) paratropical to warm-temperate areas, and in arid regions. The coral faunas of the Valanginian are distinctly dominated by corals of well-established microstructural groups. Only 13% of the species from 24% of the genera belong to “modern” groups. Compared to the situation in the Berriasian which showed that 9% of the species and 17% of the genera belonged to modern microstructural groups, the occurrence of “modern” groups significantly increased during the Valanginian.

Introduction

Lower Cretaceous scleractinian corals are known from a vast number of occurrences worldwide, especially for the period Hauterivian–middle Albian (e.g., Baron-Szabo, 1993, 1997, 2014, 2016, 2021a, 2021b; Baron-Szabo & Fernández-Mendiola, 1997; Baron-Szabo & González-León, 1999, 2003; Baron-Szabo & Steuber, 1996; Bover-Arnal, et al., 2012, Bugrova, 1990, 1999; Dietrich, 1926; Eguchi, 1951; Felix, 1891; Filkorn & Pantoja-Alor, 2009; Idakieva, 2007; Karakash, 1907; Koby, 1896, 1897, 1898; Kuzmicheva, 2002; Löser 2008; Löser, et al., 2015; Morycowa, 1964, 1971; Morycowa & Decrouez, 2006; Morycowa & Marcopoulou-Diacantoni, 2002; Morycowa & Masse, 1998; Pandey et al., 2007; Prinz, 1991; Reig Oriol, 1994; Reyeros de Castillo, 1983; Schöllhorn, 1998; Scholz, 1979, 1984; Shishlov, et al., 2020; Sikharulidze, 1977, 1979, 1985; Tomás et al., 2008; Toula, 1889; Turnšek, 1997; Turnšek & Buser, 1974, 1976; Turnšek & Mihajlović, 1981; Turnšek, et al., 1992; Von der Osten, 1957; Wells, 1932, 1933, 1944). For the lowermost Cretaceous, however, only a very small number of coral assemblages have been recorded, including European faunas of the Berriasian, e.g., southern Spain (Geyer & Rosendahl, 1985), Ukraine (Arkadiev & Bugrova, 1999; Kuzmicheva, 1972), western Austria and northeastern Switzerland (Baron-Szabo, 2018; Baron-Szabo & Furrer, 2018), as well as Asia (e.g., Tibet: Liao & Xia, 1994) and northern Africa (Beauvais & M’Rabet, 1977) (for discussions on Berriasian assemblages see Baron-Szabo, 2018). A small number of coral faunas from the Valanginian have been reported, including rare European and West Asian coral assemblages such as the ones from Bulgaria (Roniewicz, 2008), Hungary (Császár & Turnšek, 1996), and Ukraine (Kuzmicheva, 1967, 2002). Recently, the first works on the Lower Cretaceous corals from Argentina (Neuquén Basin) have been published, including material from the upper Valanginian (Agrio Formation) (Garberoglio et al., 2020, 2021). In addition, the first information on upper Valanginian material from northeastern Switzerland (Pygurus Member) has been reported from an ongoing study of the Pygurus coral fauna (Baron-Szabo & Furrer, 2018). While the results of these studies are yet to be finalized, they provide sufficient information to make some initial assessments. With regard to the latter study, the material found so far shows correspondence to some stylophyllid specimens of the assemblage of the Vitznau Marl. Regarding the Argentinian fauna, representatives of well-established microstructural groups such as actinastreids have been recorded (e.g., cf. Enallocoenia [referring to material assigned in Garberoglio, et al., 2020, to Stelidioseris gibbosa] and cf. Columactinastraea [referring to material assigned in Garberoglio, et al., 2021, to Eocolumastrea octaviae]).

With regard to Valanginian corals from Switzerland, only a very small number of occurrences have been known from central and western Switzerland (Haefeli, et al., 1965; Koby, 1896, 1897, 1898). Up to now, the only taxonomic descriptions and illustrations of Swiss scleractinian corals from this time period were published more than a century ago (Koby, 1896, 1897, 1898). Recently, as a part of a book project on fossils derived from the Cretaceous sediments in the Alpstein (Kürsteiner & Klug, 2018), the first Valanginian corals were collected from northeastern Switzerland. The purpose of this paper is to (i) taxonomically describe the first scleractinian coral assemblage from the lower Valanginian of the Vitznau Marl of northeastern Switzerland; (ii) provide both preliminary paleogeographic distributional patterns and paleoenvironmental occurrences, and (iii) provide a preliminary comparison of the coral fauna of the Vitznau Marl with contemporaneous scleractinian assemblages.

Materials, methods, abbreviations

Materials

In the current paper, 64 corals from the Vitznau Marl of northeastern Switzerland were identified by examining the corallum surface and using polished surfaces and thin sections. In general, the specimens are fragmented, their size ranging between several millimeters to around a decimeter. In most of the specimens, microstructural features are not preserved.

The material was collected by the coauthors Peter Kürsteiner (Nature Museum, St. Gallen), Karl Tschanz (Zurich) and Swiss collector Robin Näf (Wildhaus) during the years 2018 and 2020. Preparation of polished slabs and thin sections was carried out by Karl Tschanz. Material used in the current study is housed at the Nature Museum St. Gallen (inventory acronym of the Kürsteiner collection is NMSG Coll. PK). Further material mentioned in the current work is housed at the following institutions: MNHN: Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France; NMNHS: Natural Museum of Natural History, Sofia, Bulgaria; SNSB-BSPG: Bayerische Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und historische Geologie, Munich, Germany.

Methods

Identifications in the literature without descriptions or illustrations which have not been subsequently confirmed in taxonomic publications are excluded from taxonomic evaluation in the current work. Also excluded from a detailed comparison with other Valanginian faunas is a small number of works in which the stratigraphic ranges of the coral-bearing strata are not clearly defined but only given as, e.g., upper Berriasian–Valanginian, Valanginian–Hauterivian. These works refer to studies in the USA (Texas, Knowles Limestone; Scott, 1984; see stratigraphic update in the report by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management [BOEM], 2012, p. 19 at: www.boem.gov); Armenia (Papoyan, 1982, 1989); Norway (Baron-Szabo, 2005); Poland (Kołodziej, 2003); South Africa (Kitchin, 1908); and Spain (Geyer & Rosendahl, 1985). However, in order to provide an idea about taxa which might eventually turn out to be of Valanginian age, a list of these coral occurrences is given in Appendix Table 5.

With regard to the size of corallites, the mean value is used when polypar size overlapped two categories.

Abbreviations

*=first description of taxon to which the assignment of specimen refers; v=material was studied by one of the authors (RBS); (v)=material not examined by author but considered to be sufficiently documented to be reliably identified; citation in italics in synonymy list= taxon only listed in the work concerned (neither illustration nor description provided).

Northeastern Switzerland (Cantons of Appenzell Innerrhoden, Appenzell Ausserrhoden, and St. Gallen) (Fig. 1):

-

Alpstein (mountain chain stretching over the Cantons of Appenzell Innerrhoden, Appenzell Ausserrhoden, and St. Gallen): 20–25 km south of St. Gallen.

-

Rotsteinpass (mountain pass in the Alpstein; Cantons of Appenzell Innerrhoden and St. Gallen): located about 2 km south-southeast of Säntis.

-

Säntis (highest mountain of the Alpstein; located about 18 km south of St. Gallen.

-

Wart (Alp in the Alpstein): located about 4 km southwest of Säntis.

Lithology and sedimentary environment of the Vitznau Marl

The Vitznau Marl is characterized by a succession of hemipelagic marl containing quartz-sand turbidites (Burger, 1985, 1986; Burger & Strasser, 1981; Föllmi, et al., 2007). It is underlain by a mixed sedimentation phase (Palfris Formation and the upper part of the Őhrli Formation [upper Őhrli Limestone]) and overlain by purely calcareous sediments of the Betlis Formation and Diphyoides Limestone (Fig. 2). In northeastern Switzerland, the Vitznau Marl is represented by a 130 m thick limestone–marl alternation that is fossiliferous and clay-rich in its lower section, containing crinoids and bryozoans. In addition, sparse reworked corals and sponges were found. These layers are followed by quartz-sand-rich and fossil-poor beds (Funk, 1999; Morales, et al., 2013; Sala, et al., 2014). In the Alpstein area, the Vitznau Marl crops out south of the area of the Rotsteinpass (Sala, et al., 2014) (Fig. 3). The Vitznau Marl represents deposits of the distal shelf in the open marine area of a platform along the northern margin of the Tethys (Jordi, 2012) (Fig. 4). Geographically, the Vitznau Marl stretches from western Austria (Vorarlberg), over eastern Switzerland to the Bernese Highlands in central-western Switzerland.

Time–space diagram of the sedimentary succession of the upper Berriasian to lower Valanginian in the Helvetic Alps. The space axis represents approximately 30 km in its totality (modified from Föllmi et al., 2007). Ls = limestone; Mb = member; Fm = formation

European Valanginian shorelines. Stipple indicates land areas; asterisk = area from which the corals of the Vitznau Marl were derived (modified from Tyson & Funnell, 1987). The paleocoordinates of the collecting site are: 38° 11’ N, 18° 10’ E (paleocoordinates estimated using information available on Paleobiology Database [paleobiodb.org])

The corals found in the Vitznau Marl are represented by fragmented coralla that were reworked and re-deposited. None of the specimens were found in situ. The coral material is embedded in a fine-grained matrix together with other mm- to cm-size bioclasts such as fragmented gastropods, serpulids, sponges, shell fragments, and others.

General attributes of the corals of the Vitznau Marl at Wart (Table 1)

Morphology

The coral material described in the current work comprises 64 specimens belonging to 18 species from 17 genera and 13 families. The fauna is distinctly dominated by forms belonging to the category of lowest to no polyp integration. Half of the fauna (50%) belong to this category (branching [6 species = 33%] and solitary [3 species = 17%]). This group is followed by species having types of polyp integration of the next higher integration arrangement (cerioid-plocoid group), to which a third of the coral species belong (6 species = 33%). The smallest group of colonial forms (3 species = 17%) consists of species having the highest polyp integration (thamnasterioid), including one showing mixed types of polyp integration combining high and lower integration arrangements (the cerio-thamnasterioid Thamnoseris cf. carpathica). The main morphotypes of non-branching corals from the Vitznau Marl are massive to subhemispherical. The branching species are phaceloid (Table 1).

Corallite size and polyp integration

With regard to polypar size, the Wart fauna is almost equally distributed by species with large-size (> 9 mm) polyps (7 species; 39%) and medium-size (> 2.5‒9 mm) polyped corals (6 species; 33%), followed by corals having small-size polyps (5 species = 28%). The group with large polyps is characterized by the category of corals having lowest to no polyp integration. All of the solitary corals (3 species: Axosmilia villersensis, Montlivaltia truncata, Stylophyllid indet. [questionably solitary]) and half of the branching types (3 species: Aplosmilia semisulcata, Dermosmilia sp., Placophyllia cf. florosa) belong to this group. The only species having a higher type of polyp integration in this group is Complexastrea zolleriana which belongs to the cerioid-plocoid category. No species having highly integrated polyps (thamnasterioid) has large polyps. It should be noted, however, that several representatives of the cerioid-plocoid species Complexastrea zolleriana found in the Vitznau Marl show growth forms that closely resemble the kinds of the lowest (branching) or no polyp integration, mimicking solitary, phaceloid, and subbranching-flabellate types. The medium-size group consists of branching (3 species: Placophyllia cf. dianthus, Pleurophyllia sp., Stylophyllopsis silingensis), cerioid-plocoid (2 species: Cyathophora claudiensis, Latiastrea mucronata), and thamnasterioid (1 species: Thamnoseris cf. carpathica) forms. Species having small-size corallites form the smallest group and belong to higher polyp integration categories, including 3 species of the cerioid-plocoid (Actinastrea pseudominima, Adelocoenia parvistella, Heterocoenia inflexa) and 2 species (Actinaraea tenuis, Fungiastraea lamellosa) of the thamnasterioid groups. Neither solitary nor branching species were found in the group having small-size polyps (Table 1).

Paleoecology of the corals of the Vitznau Marl

Among other skeletal features, the corallite size found in corals has been used for paleoenvironmental interpretations (Baron-Szabo, 2021a, 2021b; Baron-Szabo & Sanders, 2020; Dimitrijević, et al., 2020; Sanders & Baron-Szabo, 2005 [and references therein]; Santodomingo, 2014). In the fauna of the Vitznau Marl, corallite size of the corals varies from less than 1 mm to more than 20 mm but smaller corallites are less common. Forms having medium- to large-size corallites are most abundant (13 species = 72%). Only 5 species (28%) belong to the small-polyp group. Furthermore, Wart corals belonging to the category consisting of forms having lowest to no polyp integration (solitary and branching types) form the most dominant group (50%), followed by species having types of polyp integration of the next higher integration arrangement (cerioid-plocoid group; 33%). Species having the highest polyp integration (thamnasterioid; 3 species = 17%) form the smallest group. Interestingly, several species belonging to the medium- and high-polyp integration groups show pseudo-branching morphotypes: (1) some specimens belonging to Complexastrea zolleriana (= cerioid-plocoid, large-polyp category) have growth forms closely resembling branching to uniserially flabellate types as are typical of genera such as Thecosmilia (= branching-phaceloid) and Latiphyllia (= subbranching to flabellate, generally uniserial); and (2) some specimens belonging to the cerioid-plocoid (small- to medium-polyps; Actinastrea and Latiastrea) and thamnasterioid (Actinaraea) categories are ramose to subcolumnar. Recent zooxanthellate coral assemblages are characterized by high-integrated species predominantly having smaller corallite diameters (1–5 mm) (Coates & Jackson, 1987; Stafford-Smith, 1993), thus significantly differing from the Wart fauna. According to, e.g., Bak and Elgershuizen (1976), Logan (1988), and Stafford-Smith (1993), corals having large-size corallites effectively reject sediment up to fine gravel-size, whereas small-polyped corals can be effective in rejection of clay to silt. In the fossil record, coral faunas characterized by species with small polyps have been reported from, e.g., the marls of the Upper Cretaceous Gosau Group (e.g., Baron-Szabo, 1997, 2003, 2014; Beauvais, 1982), from marly sediments of the Maastrichtian of Jamaica (Baron-Szabo, 2008), and from the marly to sandy-marly strata of the Oligocene of Italy (Crosara-horizon; Pfister, 1980). Coral assemblages characterized by large-size corallites rejecting sediment up to fine gravel-size have been described from the Miocene of the Caribbean (Montebello Member, Lares Formation; Champagne, 2010). From that it can be said, as a trend, that the corals of the Vitznau Marl might have been predominantly affected by coarse, up to gravel-size sediment. Considering that (1) solitary forms together with half the number of the low-integrated taxa (branching types) form the largest group; (2) even corals belonging to taxa of higher types of polyp integration developed pseudo-branching growth forms (e.g., Complexastrea zolleriana); and (3) some specimens of the cerioid-plocoid Complexastrea zolleriana that correspond to the “Coenotheca-stage” show close resemblance to mobile forms which are known for their high resilience to ecostress (e.g., Manicina areolata (Linnaeus, 1758) (Ginsburg, 1972; cf. Sanders & Baron-Szabo, 2005), the Wart fauna closely corresponds to coral assemblages that are subjected to near-chronic, moderate sediment-turbidity stress that is punctuated by high-stress events, and that are largely or entirely heterotrophic (Dryer & Logan, 1978; Sanders & Baron-Szabo, 2005). Generally, no coral fabric was observed that would suggest a biohermal development but in a very small number of places, structures are present which might be fragments of crusts of microbialites, pointing to the hypothesis that at least some corals of the Vitznau Marl might have formed some kind of bioconstruction. This implies, as a hypothesis, that the Wart fauna might have been a non-reefal, azooxanthellate community with some indication that at least a small number of corals were involved in early biohermal developments (“pioneer stage”). This closely corresponds to earlier findings showing the great range of tolerance of most of the Wart taxa (Table 1). Coral assemblages that are comparable to the Swiss fauna have been reported from various time periods such as the middle Jurassic of east-central Iran (Baghamshah Formation, Bathonian‒middle Callovian; Pandey & Fürsich, 2003) and the uppermost Lower Cretaceous of the USA (Smeltertown Formation, Albian; Turnšek, et al., 2003). At the Iranian locality, coral associations were reported from marly-silty to strongly silty-sandy sediments in mainly non-reefal and (one) biohermal development (patch-reef). The corals from the Albian Smeltertown Formation were derived from a sedimentary succession that gradually shallows from offshore marine conditions to a hyposaline lagoonal paleoenvironment with sedimentation shifting from dark-grey shale to clastic turbiditic material and resedimented carbonates. The corals were found at the base of a non-reefal shallowing-upward cycle.

Distribution of the corals of the Vitznau Marl

The corals of the Vitznau Marl are dominated by forms that are restricted to the Lower Cretaceous (9 taxa = 50%), followed by species that had their first occurrence in the Jurassic (7 taxa = 39%). Only 2 species (11%) have been known from Lower and Upper Cretaceous strata, both of which belong to the category of high-polyp integration (thamnasterioid group) (Actinaraea tenuis, Thamnoseris carpathica). No coral species of the new material occurred in strata that are both older and younger than the Lower Cretaceous (Table 2).

At the species-level, when compared to the six largest Valanginian faunas recorded, the fauna of the Vitznau Marl shows no or very little affinities to any of them (Hungary, followed by the associations of Ukraine, Switzerland [non-Vitznau Marl], of southern Spain [SpII; lower Valanginian], and Bulgaria [all between 1.3‒4.3%]). None of the species are shared with the upper Valanginian fauna of southern Spain (SpI) (Table 3; Appendix Table 8).

At the genus-level, the fauna of the Vitznau Marl shows correspondence to all six Valanginian faunas that are used for more detailed comparison at very low to low ranges. The closest correspondence is to the fauna of Spain (SpII; 14.5%), followed by the assemblages of Hungary, Bulgaria, Ukraine, Switzerland (non-Vitznau Marl), and southern Spain (SpI) (all between 3.5‒11.5%). Only two genera are shared with the fauna of Switzerland (non-Vitznau Marl), both of which are solitary forms (Axosmilia, Montlivaltia) (Table 4).

Valanginian coral assemblages worldwide

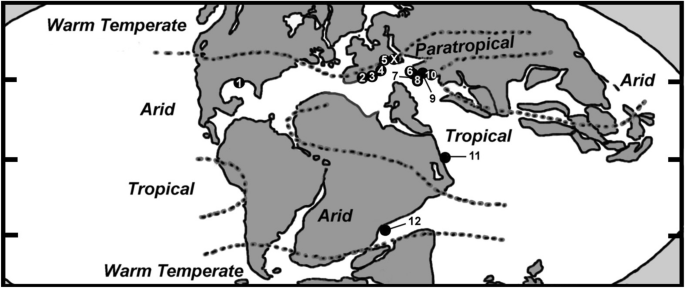

Though scleractinian coral assemblages of the Valanginian have been reported from a rather small number of localities (probably less than two dozen), they, however, have been known worldwide (Fig. 5). In the current work, in addition to the Wart fauna, twelve Valanginian coral faunas are reviewed, six of which are compared in more detail with the coral fauna of the Vitznau Marl: Ukraine (Kuzmicheva, 1967, 1985, 2002); western-central Switzerland (non-Vitznau Marl; Fromentel, in Fischer, 1873; Haefeli, et al., 1965; Jaccard, 1893); southern Spain (two faunas [Sp (I) and Sp (II)]; Löser et al., 2019, Löser et al., 2021); Hungary (Császár & Turnšek, 1996); and Bulgaria (Roniewicz, 2008).

Map showing localities of Valanginian coral faunas included in this study. X = Wart (Vitznau Marl) corals (current paper), 18 species; 1 = Mexico (Sandy, 1990; Wells, 1946), 3 species; 2 = Spain [II] (Löser, et al., 2021), 42 species; 3 = Spain [I] (Löser, et al., 2019), 19 species; 4 = France (Masse, et al., 2009), 2 species; 5 = Switzerland (non-Vitznau Marl) (de Fromentel, in Loriol, 1868; Haefeli, et al., 1965; Jaccard, 1893; Koby, 1896, 1897, 1898), 21 species; 6 = Slovenia (Turnšek, 1997; Turnšek & Buser, 1974), 3 species; 7 = Hungary (Császár & Turnšek, 1996), 29 species; 8 = Bulgaria (Roniewicz, 2008), 62 species; 9 = Poland (Lefeld, 1968), 1 species; 10 = Turkey (Kaya et al., 1987), 2 species; 11 = Ukraine (Kuzmicheva, 1967, 1985, 2002), 18 species; 12 = Tanzania (Dietrich, 1926; Löser, 2008), 7 species (for coordinates and paleocoordinates see caption of Fig. 6)

The number of species of each of these assemblages ranges from 18 (Ukraine) to 62 (Bulgaria) (Table 3). Taking into consideration the overall low numbers of both the Valanginian coral assemblages and coral taxa, as a trend it can be said as a preliminary conclusion that:

-

a total of 206 coral species belonging to 97 genera were found in the coral assemblages of the Valanginian (Appendix Tables 7 and 8);

-

at both the genus- and the species-levels, colonial taxa are most abundant during the Valanginian (colonial genera: 89%; colonial species 90%);

-

the vast majority of the Valanginian genera already occurred in older strata. Only 11 genera (out of 97 = 11%) are newly recorded, eight of which are endemic during the Valanginian (marked by *; also see Appendix Table 7): Agathelia*, Confusaforma*, Eugyra*, Lyubasha*, Microsolenastraea*, Palaeopsammia*, Paretallonia, Siderastreites*, Siderofungia*, Thalamocaeniopsis, and Tricassastraea (Lathuilière, 1989; Paleobiology Database at paleobiodb.org; and updated herein);

-

based on the succession of microstructural groups, Roniewicz and Morycowa (1993) distinguished four stages in the history of Scleractinia: I. Early Mesozoic stage; II. Middle Mesozoic stage; III. Late Mesozoic stage; and IV. Cenozoic stage. In this model, the Valanginian period belongs to phase 2 of the Middle Mesozoic stage (Oxfordian–Valanginian). This stage is characterized by (1) the continued presence of earlier microstructural types (types having rather thick trabeculae, such as haplaraeids, comoseriids, latomeandrids, and thecosmiliids; and small-to-medium size trabeculae forms, such as the actinastreids); (2) the diversification of auricular (stylinid) and amphiastreid corals; and (3) the appearance of new microstructural types such as minitrabeculae (as in Myriophyllia), as well as types forming densely branching trabeculae (as seen in neo-rhipidicanth and rhipidogyrid taxa), and groups having thick and horizontally (= parallel to corallum base) arranged trabeculae (heterocoeniids). According to Roniewicz and Morycowa (1993), a sharp limitation of microstructural development of all but newly established coral groups occurred after the Tithonian. From that it can be concluded that the scleractinian coral faunas of the Valanginian are distinctly dominated by corals of well-established microstructural groups: only 27 species (out of 206 = 13%) from 23 genera (out of 97 = 24%) belong to “modern” groups (Appendix Tables 7 and 8);

-

in a recent work on the worldwide occurrence of Berriasian corals (Baron-Szabo, 2018), 113 species belonging to 57 genera were identified. It was found that 10 species (9%) from 10 genera (18%) were representatives of modern microstructural groups. From that it can be said that the number of “modern” taxa significantly increased in the Valanginian by 33% (genus-level) and 44% (species-level), respectively;

-

all of the most-widespread genera during the Valanginian (= reported from three or more localities) belong to well-established microstructural groups (Actinaraea*, Actinastrea*, Adelocoenia*, Ahrdorffia, Axosmilia*, Cladophyllia*, Comoseris*, Cyathophora*, Dimorphastrea*, Ellipsocoenia*, Heliocoenia*, Latiastrea*, Microphyllia, Microsolena, Montlivaltia*, Periseris*, Placophyllia*, Stylina, Stylosmilia*, Synastrea, Tricassastraea) (Appendix Table 7), 15 of which (marked by *) were reported from a wide latitudinal range, including tropical to warm-temperate regions. The genera Actinastrea, Dimorphastrea, and Montlivaltia were additionally reported from arid areas (Fig. 6);

Fig. 6

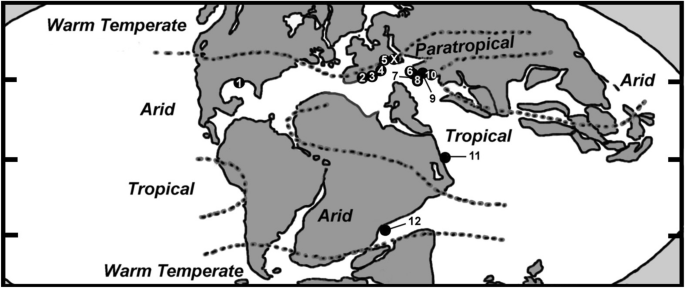

modified from Paleomap project Scotese [2014] at www.scotese.com; and Tennant, et al., 2017). Paleocoordinates of the coral localities of Spain [I, II] and Vitznau Marl at Wart estimated based on information provided by Paleobiology Database (paleobiodb.org); all others retrieved from Paleobiology Database (paleobiodb.org)

Simplified Lower Cretaceous paleogeographic map showing the occurrences of species during the Valanginian: X = Wart (Vitznau Marl) corals (current paper); 1 = Mexico (Sandy, 1990; Wells, 1946); 2 = Spain [II] (Löser, et al., 2021); 3 = Spain [I] (Löser, et al., 2019); 4 = France (Masse, et al., 2009); 5 = Switzerland (non-Vitznau Marl) (de Fromentel, in Loriol, 1868; Haefeli, et al., 1965; Jaccard, 1893; Koby, 1896, 1897, 1898); 6 = Slovenia (Turnšek, 1997; Turnšek & Buser, 1974); 7 = Hungary (Császár & Turnšek, 1996); 8 = Bulgaria (Roniewicz, 2008); 9 = Poland (Lefeld, 1968); 10 = Turkey (Kaya, et al., 1987); 11 = Ukraine (Kuzmicheva, 1967, 1985, 2002); 12 = Tanzania (Dietrich, 1926; Löser, 2008). Note that the coordinates (and paleocoordinates) of the Valanginian localities are: 1 = 25º 30 ‘ N, 103º 30 ‘W (23º 6 ‘N, 56º 30 ‘ W); 2 = 38º N, 3º W (29º N, 2º E); 3 = 38º N, 1º W (29º N, 7º E); 4 = 43° 12’ N, 5° 24’E (34° 12’ N, 14° 30 E); 5 = 47º N, 7º E (28º N, 16º E); 6 = 46° N, 13° 42’ E (31° 6’ N, 21° 6’ E); 7 = 46° 12’ N, 18° 18’ E (28° 24’ N, 24° 42’ E); 8 = 42° 48’ N, 22° 48’ E (24° 0’ N, 25° 24’ E); 9 = 50° 0’ N, 19° 48’ E (31° 0’ N, 28° 18’ E); 10 = 40° 48’ N, 29° 24’ E (36° 36’ N, 36° 54’ E); 11 = 44° 48’ N, 34° 30 E (0° 30’ S, 49° 30 E); 12 = 9° 42’ S, 39° 18’ E (31° 48’ S, 18° 48 E); X = 47° 14′ 36″ N, 9° 21′ 55″ E (38° 11’ N, 18° 10’ E). Paleomap

-

the occurrence of taxa belonging to modern microstructural groups is nearly exclusively restricted to tropical–subtropical (= assemblages of Bulgaria, Hungary, Slovenia, Spain [I], Spain [II], Ukraine) and arid regions (Mexico). Only two modern-group taxa (the branching form Aplosmilia semisulcata and the cerio-plocoid Heterocoenia inflexa) were found in a (sub-) paratropical to warm-temperate region (Wart fauna, Vitznau Marl) (Appendix Tables 7 and 8);

-

at the genus-level, taxa belonging to modern microstructural groups were nearly or completely isolated geographically: representatives of Starostinia only occurred in the fauna of Slovenia, forms of Columnocoenia and Diplocoenia occurred in the assemblages of both Hungary and Ukraine, and the faunas of Spain (SpI) and Mexico contain species of Paretallonia. All of their respective species are endemic during the Valanginian (Appendix Table 8);

-

at the species-level, all of the forms which occurred in more than one locality during the Valanginian belong to well-established microstructural groups (Actinaraea tenuis, Ahrdorffia ornata, Axosmilia villersensis, Comoseris jireceki, Cyathophora claudiensis, Cyathophora hexalobata, Dimorphastrea explanata, Ellipsocoenia haimei, Latiastrea mucronata, Periseris lorioli) (Appendix Tables 7 and 8);

-

the Valanginian faunas having the largest numbers of solitary taxa lived in both (sub-) paratropical to warm-temperate areas (Switzerland [coral faunas of Wart [Vitznau Marl] and non-Vitznau Marl]; France) and in arid regions (Mexico, Tanzania) (paleogeography, paleoclimate, and paleoceanography data retrieved from Tennant, et al., 2017 and Paleomap project at www.scotese.com);

-

with regard to the six Valanginian faunas used for more detailed comparison, they either completely consist of or are dominated by colonial coral genera/species, ranging from 67%/76% (western-central Switzerland [non-Vitznau Marl; SII]) to 100% (Spain [SpI]) (Appendix Table 6);

-

at the species-level, the six Valanginian coral faunas from which the largest number of corals were recorded are distinctly dominated by taxa that are endemic in the Valanginian (Table 3; Appendix Tables 7 and 8), which is in great contrast to the distributional patterns of both the Upper Jurassic and most of the post-Valanginian Lower Cretaceous faunas (Hauterivian–Middle Albian). While many Jurassic and post-Valanginian assemblages are characterized by cosmopolitan to subcosmopolitan taxa (for the Jurassic, see, e.g., Beauvais, 1973, 1989; Errenst, 1990, 1991; Lathuilière, et al., 2020; Morycowa, 2012; Roniewicz, 1976; Turnšek, 1997; for the Lower Cretaceous, see e.g., Baron-Szabo, 2014, Baron-Szabo, 2021b; Baron-Szabo & González-León, 2003; Morycowa, 1971; Morycowa & Masse, 1998, 2009; Morycowa & Marcopoulou-Diacantoni, 2002; Pandey et al., 2007; Turnšek, 1997), the Valanginian faunas appear largely isolated (Table 3).

Systematic paleontology

The taxonomic framework applied here is based on the works by Milne Edwards and Haime (1857), Duncan (1884), Vaughan and Wells (1943), Alloiteau (1952, 1957), Wells (1956), Eliášová (1990), Baron-Szabo (2014, 2021c) for higher-level taxa (family), with updates on individual genera and species by Baron-Szabo (2014, 2021b) and Morycowa and Roniewicz (2016). Because the suborders of Vaughan and Wells (1943) are neither monophyletic nor do they conform with recent molecular results, they are no longer useful and are, therefore, excluded from the taxonomic framework. Because the taxonomy of scleractinian corals is in a transitional phase (Scleractinian Treatise is in progress; an increasing number of contradicting taxonomic approaches have been applied [see discussion in Kołodziej & Marian, 2021]; etc.), in the current work, the taxonomic framework is based on levels no higher than family (excluding superfamily and higher). For further information on excluded taxonomic frameworks of scleractinian corals see Baron-Szabo (2021b).

Family Actinastreidae Alloiteau, 1952

Remarks.

In some recent publications (e.g., Garberoglio, et al., 2020; Löser, 2012), material was grouped with the family Actinastreidae that showed characteristics of families such as Columastreidae, Cladophylliidae, and others (e.g., Baron-Szabo, 2014, p. 20; and discussion in Baron-Szabo, 2021b under Cladophyllia crenata). Therefore, a combination of the family concepts by Alloiteau (1954) and Baron-Szabo (2014) is followed.

Genus Actinastrea d’Orbigny, 1849

Type species. Actinastrea goldfussi d’Orbigny, 1850a, 1850b, Maastrichtian of The Netherlands (Maastricht).

Diagnosis. Corallum colonial, often massive to subcolumnar, cerioid, cerio-plocoid. Budding extracalicular and extracalicular-marginal. Corallites small and prismatic in outline, often directly united by their walls. Columella styliform or short-lamellar. No intercalicinal coenosteum. Synapticular structures present peripherally. Paliform structures occasionally present. Endothecal dissepiments thin, sometimes arranged forming an inner-corallite ring which is complete or incomplete. Septa compact, generally non-confluent, radially or bilaterally arranged, beaded marginally, and composed of a series of simple trabeculae, varying in diameter (up to 150 µm). Septal flanks covered by spiniform granulae. Wall septothecal to septoparathecal, with occasionally occurring pores (lacunes).

Actinastrea pseudominima (Koby, 1897 )

Fig. 7A

A Actinastrea pseudominima (Koby, 1897), NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.33c; calicular view of colony, thin section; scale bar: 1.5 mm. B Complexastrea zolleriana (Quenstedt, 1879), NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.20a; calicular view of colony in Latiphyllia-type stage, thin section; scale bar: 3.5 mm. C Complexastrea zolleriana (Quenstedt, 1879), NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.20a; upper surface of colony, lateral view; scale bar: 5 mm. D Complexastrea zolleriana (Quenstedt, 1879), NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.20b; calicular view of colony in Coenotheca–Complexastrea-type stage, thin section; scale bar: 4 mm. E Complexastrea zolleriana (Quenstedt, 1879), NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.36; calicular view of colony in Montlivaltia–Coenotheca-type stage, polished surface; scale bar: 5 mm. F Complexastrea zolleriana (Quenstedt, 1879), NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.36; calicular view of colony in Montlivaltia–Coenotheca-type stage, polished slab; scale bar: 5 mm. G Montlivaltia truncata (Defrance, 1817), NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.25a; calicular view, polished; scale bar: 3 mm. H Montlivaltia truncata (Defrance, 1817), NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.25a-I; calicular view, polished, slightly oblique; scale bar: 6.5 mm. I Montlivaltia truncata (Defrance, 1817), NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.22d; polished surface of oblique lateral-calicular view, polished; scale bar: 5 mm. J Montlivaltia truncata (Defrance, 1817), NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.25a (= 25a-I); upper surface of corallum, lateral view, slightly oblique; scale bar: 5 mm

-

v*1897 Astrocoenia pseudominima, Koby, 1896: Koby, p. 59, Pl. 15, Figs. 4–4a [topotypes studied].

-

nonv1926 Astrocoenia pseudominima Koby: Dietrich, p. 93, Pl. 6, Fig. 9.

-

v1936 Astrocoenia pseudominima Koby, 1896: Hackemesser, 1936, p. 71, Pl. 7, Fig. 14.

-

non1961 Actinastraea cf. pseudominima Koby: Bendukidze, p. 8.

-

v1964 Actinastraea pseudominima (Koby, 1896): Morycowa, p. 18–20, Pl. 1, Fig. 2–5, Pl. 2, Fig. 2.

-

v1971 Actinastraea pseudominima pseudominima (Koby, 1896): Morycowa, p. 33–37, Pl. 1, Fig. 1–2, Pl. 3, Fig. 1, Pl. 4, Fig. 1, Pl. 5, Fig. 3, Text-Figs. 6A, 11–12.

-

1977 Actinastrea cf. pseudominima (Koby, 1896): Sikharulidze, p. 69–71, Pl. 7, Fig. 1.

-

non1985 Actinastrea pseudominima (Koby, 1897): Geyer & Rosendahl, p. 167, Pl. 2, Fig. 1.

-

1988 Actinastraea pseudominima (Koby, 1896): Kuzmicheva & Aliev, p. 154, Pl. 1, Fig. 1a–b.

-

nonv1989 Actinastrea cf. pseudominima (Koby, 1896): Löser, p. 98–99, Pl. 21, Fig. 1, Text-Fig. 3.

-

nonv1992b Actinastraea pseudominima (Koby, 1896): Eliášová, 1992b, p. 402, Pl. 5, Fig. 3.

-

v1995 Actinastraea pseudominima (Koby, 1896): Abdel-Gawad & Gameil, 1995, p. 8, Pl. 4, Figs. 3–6.

-

1998 Actinastrea aff. pseudominima (Koby, 1897): Morycowa & Masse, p. 738, Fig. 10.2.

-

v2003 Actinastrea aff. pseudominima (Koby, 1897): Baron-Szabo, et al., 2003 p. 201, Pl. 36, Figs. 5–6.

-

2009 Actinastrea pseudominima (Koby, 1897): Filkorn & Pantoja-Alor, p. 23–25, Figs. 9.1–8 (older synonyms cited therein).

-

v2018 Actinastrea pseudominima (Koby, 1897): Baron-Szabo, p. 30, Pl. 1, Fig. A.

-

v2021b Actinastrea pseudominima (Koby, 1897): Baron-Szabo, p. 31, Pl. 1, Fig. C–D.

Dimensions of skeletal elements. Diameter of corallites: 1–2.2 mm, in areas of intense budding it can be 0.8 mm; distance of corallite centers: 1.1–2.7 mm; septa/corallite: 24, in corallites in areas of intense budding: 12.

Description. Small massive to subramose, cerioid to cerio-plocoid colony with often prismatic corallites. Costosepta arranged in 3 complete cycles in 6 systems in largest corallites. Columella styliform or short-lamellar. Endothecal dissepiments thin. Wall paraseptothecal to septothecal.

Type locality of species. Aptian of Switzerland (Reignier).

Distribution. Upper Berriasian (upper Őhrli Formation; Rotsteinpass, Lisengrat, Alpstein area) and lower Valanginian of northeastern Switzerland (Vitznau Marl, Wart, this paper), lower Barremian of Georgia (in Caucasia) and Turkmenistan, Barremian of Azerbaijan and Poland, upper Barremian–lower Aptian of Switzerland (Schrattenkalk Formation, Tierwis area) and France, lower Aptian of Mexico and Romania, upper Aptian of Iran, Aptian of Switzerland (Reignier), Albian of Egypt.

Material. NMSG Coll. PK–02.10.33c.

Remarks.

In having 10–12 septa, the material described as A. cf. pseudominima from the Hauterivian of Crimea in Bendukidze (1961) differs from Koby’s species. In having corallite diameters that are significantly larger than 2 mm, the material described in Dietrich (1926, p. 93) from the Lower Cretaceous of Tanzania differs from the species A. pseudominima. The specimens described from the upper Cenomanian of Germany (Löser, 1989, p. 98–99) and from the upper Cenomanian–lower Turonian of the Czech Republic (Eliášová, 1992b, p. 402) are more closely related to A. tourtiensis (Bölsche, 1871). For additional synonyms of the species A. pseudominima, see Paleobiology Database (paleobiodb.org).

Family Thecosmiliidae Duncan, 1884

Genus Complexastrea d’Orbigny, 1850b

Type species. Complexastrea subburgundiae d’Orbigny, 1850b, Jurassic (‘Corallien’) of France.

Diagnosis. Colonial, often massive to subhemispherical, subbranching to subflabellate during various stages of astogeny, present or absent. Polyp integration astreoid, plocoid to cerio-plocoid; submeandroid to thamnasterioid integration during various stages of astogeny present or absent. Budding intracalicular and extracalicular. Costosepta compact, non-confluent to confluent, granulated and carinate laterally. Their axial ends can be rhopaloid. Columella absent or formed by weakly parietal structures. No pali. Synapticulae absent. Intertrabecular distance ranging between 200 and 1300 µm. Endothecal dissepiments pass from one corallite to the next, they are vesicular, cellular, or tabuloid. Wall absent or paraseptothecal.

Complexastrea zolleriana (Quenstedt, 1879 )

Figs. 7B–F

-

*1879 Coenotheca zolleriana: Quenstedt, p. 609, Pl. 165 figs. 36-43.

-

(v)1996 Complexastrea zolleriana (Quenstedt): Lathuilière, p. 597, Pl. 72, Fig. 1–18, Pl. 73, Fig. 1–13, Pl. 74, Fig. 1–4, Pl. 75, Fig. 1–7, Text-Figs. 5–6, 8–11 [older synonyms cited therein].

-

pars(v)2003 Montlivaltia decipiens (Goldfuss 1826): Pandey & Fürsich, p. 42–43, Pl. 10, Fig. 7–10, [?Pl. 8, Fig. 6].

-

(v)2003 Latiphyllia cf. confluens (Quenstedt, 1843): Pandey & Fürsich, p. 44–46, Pl. 11, Fig. 1.

-

(v)2003 Coenotheca zolleriana Quenstedt, 1881: Pandey & Fürsich, p. 46–48, Pl. 11, Fig. 2–6.

Dimensions. Great diameter of corallites: 10–30 mm; in areas of intense budding around 8 mm; septa/corallite: up to around 100, in corallites in areas of intense budding around 20; septa/mm: 3–9/5; distance of corallite centers: 5–21 mm; septal thickness ranges between 100 and 1300 µm.

Description. Individual specimens are in various transgeneric stages including (1) cerio-plocoid to astreoid corallites in subflabellate arrangement (resembling Latiphyllia); (2) small submassive clumps consisting of a few polyps in subplocoid to submeandroid-thamnasterioid arrangement (resembling Coenotheca); and (3) tall corallum with subplocoid corallites (resembling Thecosmilia); costosepta straight to very wavy; endothecal dissepiments numerous, large vesicular peripherally, cellular to vesicular in central areas of corallum.

Type locality of species. Middle Jurassic (“Brauner Jura gamma”) of Germany (Hohenzollern).

Distribution. Middle Jurassic of France, Germany, and Iran, lower Valanginian of northeastern Switzerland (Vitznau Marl, Wart; this paper).

Material. NMSG Coll. PK–02.10.20a, 20b (= 02.10.21a), and 20c; –02.10.21c; –02.10.25a-II; –02.10.27c-A. –02.10.27c-B; –02.10.27d; –02.10.36; ?–02.10.38.

Remarks.

Based on a population study including Middle Jurassic thecosmiliid corals, Lathuilière (1996) established a morphogenesis framework for the genus Complexastrea using individuals that, with regard to the dimensions of their skeletal elements, correspond to the species zolleriana. He came to the conclusion that during various stages of astogeny forms of the genus Complexastrea show morphological overlaps with several other thecosmiliid genera such as Coenotheca, Latiphyllia, Montlivaltia, and Thecosmilia. As a result, specimens that might show close resemblance to one of these genera are grouped with Complexastrea. While this approach has not been accepted by some authors (e.g., Pandey & Fürsich, 2003), it is followed here based on the fact that the genus Complexastrea shows features that clearly distinguishes it from the genera with which it shows morphological convergence during different stages of astogeny. In having both extracalicular budding in addition to intracalicular multiplication and a paraseptothecal wall, Complexastrea differs from genera such as Latiphyllia and Thecosmilia (= characterized by intracalicular multiplication and the lack of septothecal thickenings). In its early (“solitary”) stage, Complexastrea closely resembles the solitary genus Montlivaltia but shows features such as (1) cerio-plocoid shapes and often paraseptothecal developments in the peripheral areas; (2) a rather flat to cupolate corallum; and (3) the presence of budding spots (“generator septa” and “linking septa” sensu Lathuilière [1996, Text-Fig. 10A‒B]) from which new corallites develop, closely corresponding to the situation in other genera such as the cunnolitid genus Aspidastraea which can be misinterpreted for the solitary genus Cunnolites in its early stages of astogeny (Baron-Szabo, 2003). In contrast to the “Montlivaltia”- stage of Complexastrea, the genus Montlivaltia is variably conical (rarely subdiscoidal-patellate in certain environments), and lacks both septothecal thickenings and budding spots. The genus Coenotheca very closely corresponds to the juvenile stage of Complexastrea and is, therefore, considered to be a junior synonym of Complexastrea.

Individual specimens from the Vitznau Marl correspond to different morphotypes of the species C. zolleriana. The specimen NMSG Coll. PK-02.10.20a resembles the “Latiphyllia” variation as shown in Lathuilière (1996, Pl. 72, Figs. 8 and 15, and Text-Fig. 10A–B); the specimens NMSG Coll. PK-02.10.20c, 02.10.25a-II, and 02.10.36 show close affinities to the “Coenotheca” morphotype as shown in Lathuilière (1996, Pl. 72, Figs. 7 and 10); the specimen NMSG Coll. PK-02.10.20b (= 02.10.21a) resembles the “Thecosmilia” variation as shown in Lathuilière (1996, Pl. 72, Fig. 5); the specimen NMSG Coll. PK-02.10.21c corresponds to a mix of transgeneric stages including variation of “Complexastrea–Coenotheca–Thecosmilia” as shown in Lathuilière (1996, Pl. 73, Fig. 5–8); and the specimens NMSG Coll. PK-02.10.27c-A and B, and –02.10.27d show close affinities to early stages of astogeny of Complexastrea, corresponding to a mix of “Coenotheca–Montlivaltia” morphotypes as shown in Lathuilière (1996, Pl. 72, Figs. 3 and 6).

Genus Montlivaltia Lamouroux, 1821

Type species. Montlivaltia caryophyllata Lamouroux, 1821, Middle Jurassic (Upper Bathonian) of Calvados.

Diagnosis. Solitary, trochoid to subcylindrical, or turbinate, rarely (subdiscoidal-) patellate. Costosepta compact, thin to thick, exsert, in general numerous and crowded. Columella absent. Intertrabecular distance ranging between 200 and 1300 µm. Endothecal dissepiments abundant, vesicular. Epitheca sensu lato membraniform or absent.

Montlivaltia truncata (Defrance, 1817 )

Figs. 7G–J

-

*1817 Caryophyllia truncata: Defrance, vol. 7, p. 198.

-

v1954 Montlivaltia truncata (Defrance) 1817: Geyer, 1954, p. 174 [older synonyms cited therein].

-

(v)1977 Montlivaltia truncata Defrance, 1817: Beauvais, in Beauvais & M’Rabet, p. 109, Pl. 1, Fig. 3a–b, Pl. 2, Fig. 2 [older synonyms cited therein].

-

(v)1977 Montlivaltia sioufensis nov. sp.: Beauvais, in Beauvais & M’Rabet, p. 112, Pl. 3, Fig. 1.

-

(v)1994 Montlivaltia xizangensis Liao et Xia: Liao & Xia, p. 158, Pl. 43, Figs. 9–14 and 20–23.

-

v2018 Montlivaltia truncata (Defrance, 1817): Baron-Szabo, p. 38–39, Pl. 2, Figs. I–J [older synonyms cited therein].

Dimensions. Corallite diameter at top of corallum (d x D): 12 × 18 mm (estimated); d/D = 0.67; diameter at basal part of corallum (d x D): 10 × 12 mm (estimated); d/D = 0.83; septa at top of corallum; probably 96; septa at basal part: around 40; septa/mm (peripheral area of corallite): 7–10/5; height of corallum: at least 35 mm.

Description. Incomplete solitary, turbinate, corallum; septa straight, regularly alternate in length and thickness, probably developed in 5 complete cycles in 6 systems at top of corallum; endothecal dissepiments numerous, long, mainly vesicular; membraniform epitheca sensu lato present.

Type locality of species. Upper Jurassic of France.

Distribution. Upper Jurassic of France, Germany, and Switzerland, upper Oxfordian of Azerbaijan and Georgia (in Caucasus), upper Oxfordian–lower Tithonian of Russia, Kimmeridgian of Portugal, Berriasian of central Tibet, upper Berriasian of northern Tunisia and northeastern Switzerland (upper Őhrli Formation), lower Valanginian of northeastern Switzerland (Vitznau Marl, Wart; this paper).

Material. NMSG Coll. PK–02.10.25a (= 02.10.22d).

Remarks.

Because the specimen is incomplete the full range of its dimensions of skeletal elements can only be estimated. The dimensions found in the Swiss material closely correspond to the ones of M. truncata.

The species M. truncata was recently discussed and revised (Baron-Szabo, 2018). For further synonyms of the species M. truncata, see Paleobiology Database (paleobiodb.org).

Family Placophylliidae Eliášová, 1990

Genus Placophyllia d’Orbigny, 1849

Type species. Lithodendron dianthus Goldfuss, 1827, Upper Jurassic of Germany (Giengen).

Diagnosis. Colonial, mainly phaceloid, can be subdendroid or fasciculate with plocoid to cerioid polyp outlines in younger colonies. Budding extracalicular and intracalicular-marginal. Costosepta compact, septal flanks covered by small granules. Distal edge of septa smooth. In closely packed corallites costae may be subconfluent. Columella lamellar. Synapticulae and pali absent. Intertrabecular distance ranging between 40 and 130 µm in septa. Corallite wall parathecal, irregular. Septothecal thickenings present or absent. Endothecal dissepiments vesicular in peripheral corallite areas and subtabulate in axial corallite areas. Epithecal sensu lato wall folded.

Placophyllia cf. dianthus (Goldfuss, 1826)

Figs. 8A–C

A Placophyllia cf. dianthus (Goldfuss, 1826), NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.26a; calicular view, polished surface; scale bar: 2.5 mm. B Placophyllia cf. dianthus (Goldfuss, 1826), NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.26a; calicular view, thin section; scale bar: 2.5 mm. C Placophyllia cf. dianthus (Goldfuss, 1826), NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.27a; calicular view, polished surface; scale bar: 2.5 mm. D Placophyllia cf. florosa Eliášová, 1976b, NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.28a; calicular view, polished surface; scale bar: 3 mm. E Placophyllia cf. florosa Eliášová, 1976b, NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.31a; calicular view, thin section; scale bar: 2.5 mm. F Dermosmilia sp., NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.32a; calicular view, thin section; scale bar: 3.5 mm. G Fungiastraea lamellosa (de Fromentel, 1857), NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.16b; upper surface of colony, calicular view; scale bar: 4 mm. H Fungiastraea lamellosa (de Fromentel, 1857), NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.28h; calicular view, thin section; scale bar: 2 mm. I Actinaraea tenuis Morycowa, 1971, NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.30e; calicular view of colony, thin section; scale bar: 2 mm. J Actinaraea tenuis Morycowa, 1971, NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.28e; calicular and longitudinal view of colony, polished surface; scale bar: 3.5 mm. K Latiastrea mucronata Sikharulidze, 1979, NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.22 g; calicular view of colony, polished surface; scale bar: 3 mm. L Latiastrea mucronata Sikharulidze, 1979, NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.22 g; close-up of Fig. M, scale bar: 1 mm. M Latiastrea mucronata Sikharulidze, 1979, NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.22 g; calicular view, thin section; scale bar: 2 mm

-

v*1826 Lithodendron dianthus: Goldfuss, p. 45, Pl. 3, Fig. 8.

-

v1876 Placophyllia? rugosa Beck.: Becker, p. 140, Pl. 38, Fig. 9a–b (older synonyms cited therein).

-

1985 Placophyllia dianthus (Goldfuss, 1826): Rosendahl, p. 49, Pl. 1, Fig. 10.

-

1989 Placophyllia cf. dianthus (Goldfuss): Beauvais, p. 295.

-

1990 Placophyllia rugosa Becker, 1876: Eliášová, p. 121, pl. 2, Fig. 1.

-

v1991 Placophyllia dianthus (Goldfuss, 1826): Lauxmann, p. 155, Text–Fig. 15.

-

v1997 Placophyllia rugosa Becker, 1876: Turnšek, p. 153, Figs. 153A–F.

-

2003 Placophyllia dianthus (Goldfuss, 1826): Kołodziej, p. 213, Fig. 27 [older synonyms cited therein].

-

2005 Placophyllia cf. dianthus (Goldfuss, 1826): Morycowa & Mišik, 2005, p. 420, Fig. 3.5.

-

2008 Placophyllia rugosa Becker, 1876: Roniewicz, p. 104, Figs. 6E–F.

-

v2018 Placophyllia dianthus (Goldfuss, 1826): Baron-Szabo, p. 48, Pl. 5, Fig. A–B, D–E [older synonyms cited therein].

Dimensions of skeletal elements. Diameter of corallites: 7–9 mm; number of septa: 32–36.

Description. Fragments of a phaceloid colony; corallites subcircular to subpolygonal in outline; costosepta developed in 3 to 4 size orders; lamellar columella generally attached to septa at either one or both ends of longer axis; septothecal thickenings present frequently but peripheral area of corallite often abraded.

Type locality of species. Upper Jurassic of Germany (Giengen).

Distribution. Upper Jurassic of Germany and Sumatra, Oxfordian of Slovakia, upper Oxfordian–lower Kimmeridgian of Poland, upper Oxfordian–Kimmeridgian of Georgia (in Caucasus), Russia, and Slovenia, lower Kimmeridgian of Portugal, Kimmeridgian of Croatia, Kimmeridgian–Berriasian of Bulgaria, upper Tithonian–lower Berriasian of the Czech Republic (Štramberk limestone) and Poland (Štramberk-type limestone), upper Berriasian (upper Őhrli Formation [= Oerfla Formation]) of western Austria and eastern Switzerland, lower Valanginian of northeastern Switzerland (Vitznau Marl, Wart; this paper), ?Valanginian of Poland (according to Kołodziej [2003, p. 213], material belonging to P. dianthus was collected from sediments of the Sub-Silesian Nappe, Outer Carpathians, which have a questionable Valanginian age).

Material. NMSG Coll. PK–02.10.22b; –02.10.23a (= 02.10.29a); –02.10.26a; –02.10.27a.

Remarks.

Because the Swiss material represents only small, fragmented colonies, the total dimensions of skeletal elements cannot be determined.

Placophyllia cf. florosa Eliášová, 1976b

Figs. 8D–E

-

v*1976b Placophyllia florosa n. sp: Eliášová, p. 339, Pl. 3, Figs. 1–2.

-

2018 Placophyllia cf. florosa Eliášová, 1976: Ricci, et al., 2018, p. 451–453, Pl. 7, Fig. 1a–1c.

Dimensions of skeletal elements. Diameter of corallites: 14–19 mm; number of septa: up to around 48.

Description. Fragments of a phaceloid colony; corallites subcircular to subpolygonal in outline; costosepta developed in 3 to 4 size orders; lamellar columella often thick, generally attached to septa at either one or both ends of longer axis; septothecal thickenings present frequently but peripheral area of corallite often abraded.

Type locality of species. Tithonian–lower Berriasian of the Czech Republic (Štramberk limestone).

Distribution. Kimmeridgian–Tithonian of Italy, Tithonian–lower Berriasian of the Czech Republic (Štramberk limestone), lower Valanginian of northeastern Switzerland (Vitznau Marl, Wart; this paper).

Material. NMSG Coll. PK–02.10.22c; –02.10.28a; –02.10.28b (= 02.10.30b); –02.10.31a.

Remarks.

Because the Swiss material represents only small, fragmented colonies, the total dimensions of skeletal elements cannot be determined.

Family Dermosmiliidae Koby, 1887

Genus Dermosmilia Koby, 1884

Type species. Dermosmilia crassa Dacqué, 1933, Upper Jurassic (Rauracian) of Switzerland (subsequent designation Dacqué, 1933).

Diagnosis. Colonial, dendroid, phaceloid, fasciculate, subflabellate. Corallites nearly circular to subflabellate in outline. Budding intracalicular, di- to polystomodaeal, complete. Corallites united only basally. Costosepta generally compact to subcompact, sometimes irregularly perforated, straight or irregularly wavy, laterally granulated. Anastomosis present or absent. When present, septa may be arranged during various stages of ontogeny in a pattern resembling the kinds seen in micrabaciid or dendrophylliid genera (similar to Pourtalès plan). Columella spongy-papillose or formed by fusion of trabecular prolongations of axial ends of septa. Synapticulae present. Intertrabecular distance ranging between 80 and 300 µm. Endothecal dissepiments thin, vesicular to subtabulate. Wall parathecal to parasynapticulothecal, often secondarily thickened.

Remarks.

The above given diagnosis for Dermosmilia is based on both the study of material from Caquerelle and Sante-Ursanne strata from various localities of the Koby collections housed at the museums in Basel and Bern, and the information provided by Koby (1884, p. 194–195, Pl. 50, Figs. 1–6).

Dermosmilia sp.

Fig. 8F

Dimensions. Diameter of corallite: 12 × 17 mm; septa/corallite: around 80.

Description. Fragment of a branching colony; corallite elongate in outline; septa thin, nearly equal in thickness, rather straight, developed in unclear size orders.

Material. NMSG Coll. PK–02.10.32a.

Remarks.

Because only one corallite is available, the branching angle cannot be determined. Based on the dimensions seen in the Swiss material, it could belong to species such as D. laxata, D. etalloni, or D. arborescens.

Family Haplaraeidae Vaughan & Wells, 1943

Genus Actinaraea d’Orbigny, 1849

Type species. Agaricia granulata Münster, in Goldfuss, 1829, Upper Jurassic of Germany (Nattheim).

Diagnosis. Colonial, massive, folios, thamnasterioid, including ploco- to cerio-thamnasterioid. Budding intracalicular (-marginal). Corallites embedded in a coenosteum that is generally porous to reticulate. Costosepta few in number with irregular perforations, septal flanks granular. No paliform structures. Columella generally feebly developed, parietal, lamellar, substyliform. Synapticulae present. Intertrabecular distance ranging between 80 and 180 µm. Endothecal dissepiments thin, tabulate. Wall absent or incomplete synapticulothecal.

Subgenus. Camptodocis Dietrich, 1926 (Type species. C. brancai Dietrich, 1926, Barremian–lower Aptian of Tanzania): Having the characteristics of Actinaraea but calices are not independent from perithecal colony tissue (similar as in Actinacis), corallites therefore with variably ploco- to cerio-thamnasterioid integration types.

Actinaraea tenuis Morycowa, 1971

Figs. 8I–J

-

(v)*1971 Actinaraea tenuis n. sp.: Morycowa, p. 128–130, Pl. 35, Fig. 1a–d, Pl. 36, 1a–c, Text-Fig. 37.

-

1980 Actinaraea tenuis Morycowa, 1971: Kuzmicheva, p. 106–107, Pl. 39, Fig. 4a–b.

-

non1984 Actinaraea sp. aff. A. tenuis Morycowa, 1971: Scott, p. 344, Pl. 2, Figs. 12–13.

-

1992 Actinaraea cf. A. tenuis Morycowa, 1971: Turnšek, 1992, p. 164, Fig. 2 .

-

v1996 Actinaraea tenuis Morycowa, 1971: Wilmsen, 1996, p. 361, Pl. 4, Fig. 3.

-

1996 Actinaraea tenuis Morycowa, 1971: Császár & Turnšek, p. 430, Fig. 7(6).

-

v1997 Actinaraea tenuis Morycowa, 1971: Baron-Szabo, p. 79, Pl. 12, Fig. 1–2 [older synonyms cited therein].

-

2003 Actinaraea tenuis Morycowa, 1971: Turnšek, et al., p. 179, Figs. 12A–B.

-

v2014 Actinaraea tenuis Morycowa, 1971: Baron-Szabo, p. 53, Pl. 58, Fig. 3 Pl. 59, Fig. 1–2.

-

v2021b Actinaraea tenuis Morycowa, 1971: Baron-Szabo, p. 54, Pl. 8, Fig. A.

Dimensions. Corallite diameter: 1–1.7 mm; distance of corallite centers: 2.3–4.5 mm; septa/corallite: up to around 24; septa/mm: 6–8/2; synapticulae (longitudinal view)/mm: 3–4/1.

Description. Submassive to foliose, thamnasterioid colony; corallites subdistinct to indistinct, regularly disposed over the colony; septa confluent to subconfluent; 6–8 septa reach corallite center; columella substyliform or made of a small number of thin, twisted segments.

Type locality of species. Lower Aptian of Romania (Valea Izvorul Alb).

Distribution. Lower Valanginian of northeastern Switzerland (Vitznau Marl, Wart; this paper), Valanginian of Hungary, Hauterivian of Georgia (in Caucasus), Barremian–lower Aptian of Serbia, Barremian–Aptian of Slovenia, upper Barremian–lower Aptian of western Austria (Schrattenkalk Formation, Vorarlberg), lower Aptian of Romania and southern Germany (Upper Schrattenkalk, Bavaria), middle Albian of the USA (New Mexico), lower Cenomanian of Spain, lower Coniacian of Austria (Gosau Group at Brandenberg).

Material. NMSG Coll. PK–02.10.14b; –?02.10.16a; –02.10.23e (= 02.10.29e); –02.10.26c; –02.10.26c-1; –02.10.28e; –02.10.30e; –02.10.37a.

Remarks.

Information regarding material of Scott (1984) see Appendix Table 5.

Family Latomeandridae Alloiteau, 1952

Genus Fungiastraea Alloiteau, 1952

Type species. Fungiastraea laganum Alloiteau, 1952, Upper Turonian of France (Uchaux, Vaucluse).

Diagnosis. Colonial, massive, thamnasterioid to submeandroid. Budding intracalicular, occasionally extracalicular. Corallite centers distinct. Septa compact to subcompact, confluent, moderately granulated and pennulated laterally. Sub- to non-confluent septa sparse, occurring in areas of extracalicular budding. Columella spongy, papillose, or variably shaped when columellar trabeculae fuse. Paliform structures absent. Synapticulae present. Intertrabecular distance ranging between 90 to around 350 µm. Endothecal dissepiments thin, vesicular to subtabulate. No wall between corallites but parasynapticulothecal developments circumscribing some parts of corallites sometimes present.

Fungiastraea lamellosa (de Fromentel, 1857 )

Figs. 8G–H

-

v*1857 Thamnastraea lamellosa: de Fromentel, p. 61.

-

v1887 Centastraea lamellosa: de Fromentel, 1887, p. 617, Pl. 187, Fig. 1–1c .

-

1914Centastraea lamellosa: de Fromentel: Felix, 1914, p. 55.

-

non1998 Fungiastraea lamellosa (de Fromentel, 1857): Löser, p. 180.

-

non2001 Dimorphastrea cf. lamellosa (de Fromentel, 1857): Löser, p. 46.

Dimensions. Diameter of corallites (monocentric): 2–3 mm, in areas of intense budding around 1.5 mm; distance of corallite centers: 2–4 mm; septa/corallite: 18–24 + s, in corallites in areas of intense budding around 12; septa/mm: 5–8/2.

Description. Thamnasterioid-submeandroid colony; corallites irregularly disposed or arranged in short-meandroid series; septa subequal in thickness; up to 6 septa reach corallite center; columella made of a small number of papillae or twisted segments.

Type locality of species. Lower Hauterivian of France (Yonne).

Distribution. Lower Valanginian of northeastern Switzerland (Vitznau Marl, Wart; this paper), lower Hauterivian of France (Yonne).

Material. NMSG Coll. PK–02.10.16b; –02.10.28h.

Remarks.

In having larger dimensions of skeletal elements (corallite diameter: 2.5–4 mm; septa/corallite: 25–30; septa/mm: 8/2), the material from the lower Cenomanian of Germany provisionally assigned to lamellosa in Löser (1998) differs from de Fromentel’s species. In forming a dimorphastreid corallum and having smaller dimensions of skeletal elements (septa/corallite: 16–20 (24); septa/mm: 5–6/2), the material from the lower Hauterivian of France provisionally assigned to the species lamellosa in Löser (2001) differs from de Fromentel’s species. The Swiss material corresponds well to the syntype of the species F. lamellosa (MNHN.F.M03558).

Genus Latiastrea Beauvais, 1964

Type species. Latiastrea foulassensis Beauvais, 1964, Upper Jurassic (Kimmeridgian) of France (Valfin-les-Saint-Claude).

Diagnosis. Colonial, massive, cerioid to meandroid. Budding intracalicular. Corallites prismatic, elongate, monocentric, or temporarily dicentric (to ?polycentric) during budding processes, or arranged in meandroid series. Costosepta non-confluent to subconfluent, with rare perforations on axial ends of septa. Anastomosis present. Rudimentary young septa alternate with old ones. Septal flanks are ornamented with large, spiniform granulae. Pennulae present. Distal margins covered with small, regularly developed rounded denticles. Synapticulae present. Columella parietal-spongy, sometimes forming elongate segments. Intertrabecular distance ranging between 100 to around 200 µm. Endothecal dissepiments thin, vesicular. Wall synapticulothecal and septothecal.

Latiastrea mucronata Sikharulidze, 1979

Figs. 8K–M.

-

(v)*1979 Latiastraea mucronata Sikh., sp. nov.: Sikharulidze, p. 37, Pl. 3, Fig. 4–4a, Pl. 23, Pl. 24, Fig. 1a–b.

-

1996 Latiastraea mucronata Sikharulidze, 1979: Császár & Turnšek, p. 434, Fig. 26.

-

v1999 Latiastraea mucronata Sikharulidze, 1979: Baron-Szabo & González-León, p. 490, Fig. 6e.

-

(v)2002 Latiastrea mucronata Sikharulidze, 1979: Morycowa & Marcopoulou-Diacantoni, p. 53, Figs. 34F, G.

-

v2003 Latiastraea mucronata Sikharulidze, 1979: Baron-Szabo & González-León, p. 220, Fig. 9D, F.

-

v2018 Latiastrea mucronata Sikharulidze, 1979: Baron-Szabo, p. 66, Pl. 9, Fig. A.

Dimensions of skeletal elements. Diameter of corallite (monocentric): 2–4 mm; distance of corallite centers: 2–4.5 mm; septa/corallite (monocentric): up to around 30; septa/mm: 7–8/2.

Description. Massive, cerioid colony; septa are subequal in thickness, irregularly alternate in length; columella often made of elongate segments.

Type locality of species. Albian of Georgia (in Caucasus).

Distribution. Upper Berriasian (upper Őhrli Formation [= Oerfla Formation]) of western Austria, lower Valanginian of northeastern Switzerland (Vitznau Marl, Wart; this paper), Valanginian of Hungary, upper Aptian–lower Albian of Mexico, Albian of Georgia (in Caucasus) and Greece.

Material. NMSG Coll. PK–02.10.22e (= 02.10.30a); –02.10.22g.

Genus Thamnoseris de Fromentel, 1861

Type species. Thamnoseris incrustans de Fromentel, 1861, Middle Jurassic of France (Chaumont, Saint Claude, French Jura).

Diagnosis. Colonial, massive, hemispherical, cerio-thamnasterioid, corallites arranged in short-meandroid series present or absent. Budding extracalicular-marginal. Costosepta confluent, irregularly perforated, granulate and probably pennulate laterally. Anastomosis frequently present. Columella parietal-papillose. Synapticulae numerous. Endothecal dissepiments vesicular, thin. Intertrabecular distance ranging between 120 and ca. 240 µm. Wall synapticulothecal, incomplete.

Thamnoseris cf. carpathica Morycowa, 1971

Figs. 9A–B

A Thamnoseris cf. carpathica Morycowa, 1971, NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.37b; calicular view of colony, polished surface; scale bar: 2 mm. B Thamnoseris cf. carpathica Morycowa, 1971, NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.37b; oblique longitudinal view of colony, polished surface; scale bar: 1 mm. C Adelocoenia parvistella Alloiteau, 1961, NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.29d (= 23d); calicular view of colony, thin section; scale bar: 2 mm. D Adelocoenia parvistella Alloiteau, 1961, NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.29d (= 23d); close-up of Fig. C; scale bar: 1 mm. E Adelocoenia parvistella Alloiteau, 1961, NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.23d (= 29d); upper surface of colony, calicular view, partially polished; scale bar: 2 mm. F Pleurophyllia ? tobleri (Koby, 1896), NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.15; calicular view of corallum, polished surface; scale bar: 1 mm. G Pleurophyllia ? tobleri (Koby, 1896), NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.20d; calicular view of corallum, upper surface; scale bar: 1 mm. H Cyathophora claudiensis Étallon, 1859, NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.22a; calicular view of colony, thin section; scale bar: 4 mm. I Cyathophora claudiensis Étallon, 1859, NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.22a; upper surface of colony, calicular view; scale bar: 10 mm. J Cyathophora claudiensis Étallon, 1859, NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.29b (= 23b); calicular view of colony, thin section; scale bar: 3 mm. K Stylophyllid indet., NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.14c (=13) longitudinal view of corallum, oblique, polished surface; green arrows indicate septa; orange arrow indicates corallite wall; scale bar: 4 mm. L Stylophyllopsis silingensis (Liao, 1982), NMSG Coll. PK 02.10.35l; calicular view of colony, thin section; scale bar: 2 mm

-

v*1971? Thamnoseris carpathica n. sp.: Morycowa, p. 106–108, Pl. 28, Fig. 1a–e.

-

nonv1981 Thamnoseris carpathica Morycowa, 1971: Turnšek, in Turnšek & Mihajlović, p. 29, Pl. 31, Fig. 4–5.

-

1988 Thamnoseris carpathica Morycowa, 1971: Kuzmicheva & Aliev, 1988 p. 169, Pl. 5, Fig. 4a–b.

-

2006 Thamnoseris carpathica Morycowa, 1971: Morycowa & Decrouez, p. 810–812, Pl. 9, Figs. 5–7. [older synonyms cited therein]

-

2021b Thamnoseris carpathica Morycowa, 1971: Baron-Szabo, Appendix Tables 2–5, and 7–12.

Dimensions. Diameter of corallites: 2–4.5 mm, in areas of intense budding around 1.5 mm; distance of corallite centers: 2.5–5 mm, in areas of intense budding the distance is around 1.5 mm; septa/corallite: 20 to around 32, in corallites in areas of intense budding 12; septa/mm: 6–7/2.

Description. Fragment of a massive, cerio-thamnasterioid colony; corallites isolated or arranged in short-meandroid series; septa subequal in thickness; up to around 12 septa reach corallite center.

Type locality of species. Lower Aptian of Romania (Valea Izvorul Alb).

Distribution. Lower Valanginian of northeastern Switzerland (Vitznau Marl, Wart; this paper), Barremian of Azerbaijan, lower Aptian of Romania (Valea Izvorul Alb) and Switzerland (Upper Schrattenkalk of Hergiswil).

Material. NMSG Coll. PK–02.10.37b.

Remarks.

The material described as Thamnoseris carpathica from the Barremian–lower Aptian of eastern Serbia (Turnšek & Mihajlović, 1981) has just recently been transferred to the genus Thalamocaeniopsis, grouping it with the species Th. stricta (Milne Edwards & Haime) (see Baron-Szabo, 2021b). Because the Swiss material represents only a fragment of a colony, the total dimensions of the skeletal elements cannot be determined. The skeletal features observed correspond to the species Th. carpathica.

Family Stylinidae d’Orbigny, 1851

Genus Adelocoenia d’Orbigny, 1849

Type species. Astrea castellum Michelin, 1844, Upper Jurassic of France (neotype designation Lathuilière, et al., 2020).

Diagnosis. Colonial, massive to subhemispherical, small knobby, plocoid corallum. Septa compact, free, bicuneiform, costate, non-confluent, often straight, unequal in length, arranged mainly radially; bilateral arrangement might occur as a result of elongation of both calices and calicular fossae. Septal ornamentation very weak or smooth when covered by thickening deposits. Secondary trabecular axes irregularly emerge from the mid-septal plan toward the septal faces. Pali and synapticulae absent. Endotheca made of tabulae or tabuloid dissepiments, rarely vesicular. Peritheca made of vesicular dissepiments. Columella absent but a clear central subcircular fossa present (in neotype of type species, in one out of 32 corallites, however, structures are present which may or may not correspond to a columella). Intertrabecular distance up to around 100 µm. Wall parathecal, developed in continuity with thickening deposits of septa.

Adelocoenia parvistella Alloiteau, 1961

Figs. 9C–E

-

v*1961 Adelocoenia parvistella: Alloiteau, p. 289, pl. 9 fig. 5; pl. 10 fig. 9.

-

v1972 Pseudocoenia slovenica n. sp.: Turnšek, 1972: p. 20 and 83, Pl. 4, Fig. 1–2, Pl. 5, Figs. 1–4.

-

1976 Pseudocoenia slovenica Turnšek, 1973: Roniewicz, p. 48, pl. 5 fig. 5.

-

1981 Pseudocoenia slovenica Turnšek, 1972: Eliášová, 1981 p. 125, pl. 8 figs. 3–4.

-

1985 Pseudocoenia slovenica Turnšek: Rosendahl, p. 34, pl. 3 fig. 2.

-

1990 Pseudocoenia slovenica Turnšek, 1972 Errenst, p. 168, pl. 3 fig. 1.

-

v1997 Pseudocoenia slovenica Turnšek, 1972: Turnšek, p. 171, Figs. A–F.

-

2001 Pseudocoenia cf. slovenica Turnšek, 1972: Laternser, 2001 p. 162.

-

2002 Pseudocoenia slovenica Turnšek, 1972 Kashiwagi, et al., 2002 p. 10, fig. 5.2.

-

pars?2003 Pseudocoenia slovenica Turnšek, 1972: Pandey & Fürsich, p. 27, pl. 5 fig. 5; pl. 6 fig. 1–6.

-

non2003 Pseudocoenia cf. slovenica Turnšek, 1972: Pandey & Fürsich, p. 27, pl. 4 fig. 4.

-

2015 Pseudocoenia slovenica Turnšek: Kołodziej, 2015, p. 182.

-

v2020 Adelocoenia parvistella Alloiteau, 1961: Lathuilière, et al., p. 381–382, Figs. 15–16 [older synonyms cited therein]

Dimensions. Diameter of corallites: 1–1.8 mm; in areas of intense budding the diameter is around 0.8 mm; distance of corallite centers: 1.2–2 mm, in areas of intense budding the distance is around 0.8 mm; septa/corallite: 12 (6s1 + 6s2); costae/corallite: 12 and higher.

Description. Small massive to knobby colony; corallites circular to subcircular in outline, regularly disposed over the colony; costosepta developed in 2 complete cycles in 6 systems, regularly alternating in length and thickness; number of costae is equal to or slightly larger than number of septa; columella absent but in a small number of corallites trabecular extensions of axial ends of septa reach corallite center where they might fuse, forming a pseudo-columella.

Type locality of species. Upper Jurassic (Tithonian) of Spain (La Querola).

Distribution. Upper Jurassic of Armenia and Japan, Oxfordian of Germany and France, upper Oxfordian of Romania, Oxfordian–Kimmeridgian of Slovenia, lower Kimmeridgian of Romania, Kimmeridgian–Tithonian of Spain, Tithonian of Portugal, Tithonian–lower Berriasian of the Czech Republic and Poland, lower Valanginian of northeastern Switzerland (Vitznau Marl, Wart; new material this paper).

Material. NMSG Coll. PK–02.10.20f; –02.10.23d (= 02.10.29d); –02.10.27b; –02.10.28c and 28d; –02.10.29f; –02.10.30d; –02.10.32b.

Remarks.

In Adelocoenia parvistella, auriculae are present which clearly distinguishes it from genera such as Cyathophora (including its junior synonym Cryptocoenia). This represents an important fact, since Alloiteau (1958) also erected a species Cryptocoenia parvistella, using material from the Cretaceous of Madagascar (MNHN.F.M05039; and thin sections). Because the latter is here considered to belong to Cyathophora, the species is not a junior homonym.

Some of the specimens from the Jurassic of Iran assigned to this species A. slovenica by Pandey and Fürsich (2003, p. 27), are considered as Solenocoenia (such as material shown on their pl. 6, Fig. 5). In addition, it should be noted that these authors place within A. slovenica material having dimensions that significantly differ from A. slovenica (e.g., specimen SNSB-BSPG 1999 VIII 874: corallite diameter: 1.5–2.3 mm; and specimen SNSB-BSPG 1999 VIII 1085: corallite diameter: 1.5–2.6 mm). The consequence of such a wide grouping would be a much wider stratigraphic range for this species.

Family Amphiastreidae Ogilvie, 1897

Genus Pleurophyllia De Fromentel, 1856

Type species. Pleurophyllia trichotoma De Fromentel, 1856, Upper Jurassic of France (Mantoche).

Diagnosis. Colonial, phaceloid. Budding intracalicinal. Septa compact, smooth laterally, arranged bilaterally. One major septum extends to the axial region of the corallite. Septal cycles indistinct. Costae and columella absent. Intertrabecular distance ranging between 90 and ca. 160 µm. Endothecal dissepiments thin. Multilamellate epithecal sensu lato wall possibly present.

Pleurophyllia ? tobleri (Koby, 1896 )

Figs. 9F–G

-

parsv*1896 Cladophyllia Tobleri, Koby, 1896: Koby, p. 42, Pl. 7, Fig. 5 (non Fig. 4–4a)

-

2008 Pleurophyllia aff. cara Eliášová, 1975: Roniewicz, p. 97, Fig. 3B.

-

v2014 Pleurophyllia tobleri (Koby, 1896): Baron-Szabo, p. 82, Text–Fig. 21.

-

v2018 Pleurophyllia tobleri (Koby, 1896): Baron-Szabo, p. 81, Pl. 12, Figs. C–D [older synonyms cited therein].

Dimensions. Corallite diameters: 4–6 mm; septa/corallite (monocentric): around 16.

Description. Fragments of a branching colony; corallites very elongate in outline; septa arranged bilaterally, irregularly alternate in length and thickness.

Type locality of species. Upper Berriasian (upper Őhrli Formation) of Switzerland (Canton Uri: Schöner Culm).

Distribution. Upper Berriasian (upper Őhrli Formation; Canton Uri: Schöner Culm)–lower Valanginian of northeastern Switzerland (Vitznau Marl, Wart; this paper), Valanginian of Bulgaria.

Material. NMSG Coll. PK–02.10.15; –02.10.20d.

Remarks.

Because only colony fragments are available, the total range of dimensions of skeletal elements cannot be determined. The skeletal elements that are present correspond well to the species P. tobleri.

Family Cyathophoridae Vaughan & Wells, 1943

Genus Cyathophora Michelin, 1843

Type species. Cyathophora richardi Michelin, 1843, Upper Jurassic of France (lectotype designation Zaman & Lathuilière, 2014).

Diagnosis. Colonial, massive, columnar, hemispherical, knobby, plocoid, cerio-plocoid to cerioid in areas of closely spaced corallites. Budding extracalicular. Corallites circular to subpolygonal in outline, separated by a narrow costate peritheca. Costosepta compact, generally non-confluent to subconfluent, occasionally confluent, radially arranged. Sizes of septa range from very short (less of a quarter of the lumen size) to half the lumen size, in which case septa reach the axial region where they sometimes fuse. Axial ends of S1 are vertically discontinuous. No columella. No synapticulae. No pali. Endothecal and exothecal dissepiments tabulate, well-developed. Wall parathecal and septothecal.

Cyathophora claudiensis Étallon, 1859

Figs. 9H–J

-

*1859 Cyathophora claudiensis: Étallon, p. 479.

-

1897 Cyathophora claudiensis Ét.: Ogilvie, p. 176, Pl. 16, Figs. 11–12.

-

v1954 Cyathophora claudiensis Étallon, 1859: Geyer, 1954 p. 137, Pl. 9, Fig. 12.

-

1970 Amphiphora serannensis nov. sp.: Alloiteau & Bernier, 1970 p. 926–927, Pl. 28, Figs. 1–3.

-

1976 Cyathophora claudiensis Étallon, 1859: Roniewicz, p. 44–45, Pl. 4, Fig. 1–b [older synonyms cited therein].

-

1982 Cyathophora claudiensis Étallon, 1859: Bendukidze, 1982 p. 7, Pl. 1, Fig. 5.

-

nonv1991 Cyathophora claudiensis Étallon, 1859: Lauxmann, p. 114–115.

-

(v)2008 Cyathophora sp. 1: Roniewicz, p. 128, Figs. 16A–D.

-

2015 Cyathophora claudiensis: Kołodziej, 2015 p. 183.

Dimensions. Great diameter of corallites: 4.5–7 mm, in areas of intense budding around 3.5 mm; distance of corallite centers: 6–9 mm, in areas of intense budding the distance is around 4 mm; septa/corallite: 6 + 6 + 12.

Description. Massive to subhemispherical, plocoid to cerio-plocoid colony; corallites are circular to elongate in outline; costosepta are very short and spine-like, developed in two to three complete cycles in 6 systems.

Type locality of species. Upper Jurassic of France (Valfin).